In 2022 I want to work on that, and I want to finally kick off a project I’ve been threatening to undertake for years. Ready for my new blog’s inaugural 3300-word multimedia essay about Steven Soderbergh?

Category: Obsessions

We get by with a little dopamine from our friends

Hi. I relaunched Sext Exchange, my twitter game from 2014, as a game you can play by text message or Whatsapp. I am almost at the point where the source code is cleaned up to release, for once. It’s overengineered for what it does but I’m proud of it. Anyway, email or text me if you want the number. I love you.

Notes from the New Normish

Hi, we’re alive and fine. My privilege is as evident as ever, as my daily routine of isolation with Kat resembles what Maria called “an extended snow day,” mostly but not entirely without snow. I hurt for the sick and grieving; I worry for the essential and vulnerable; I watch Bon Appetit and experiment with vegan baking; I do my internet job and I watch out my window and wait. Here are some things that have held my interest in the last little while.

- As mentioned in asides, I read too much about menswear online and off these days. My favorite habit is to bargain-hunt for clothes from Japan on eBay, prance around the living room in them to aggravate Kat, and then secret them away so I can buy more. But the emergent result is that I’ve learned a lot about things I might have disdained ten years ago. I don’t have any special interest in James Bond, for instance, but Matt Spaiser’s blog about the tailoring of the films has taught me a ton about men’s fashion in the last sixty years. His post on how Cary Grant’s suit in North by Northwest (1959) went on to influence Bond’s costuming is a great example of the dry clarity of his writing.

- It seems like I’ve never written about Porpentine Charity Heartscape here before, which is strange, as her work has loomed large in my view and admiration for… seven years? Eight? Her work in writing and game design blends the sweet, the filthy, the transgender and transhuman, the pure and the skin-crawlingly cute in a way I find singular in every sense. If that sentence doesn’t hint at some content warnings, then I hope this one does. But that boundary is very much worth braving if you are so emotionally equipped. Her recent story “Dirty Wi-Fi” on Strange Horizons is a good introduction to her prose and perspective.

-

Despite my limited dabbling in microelectronics, I can’t follow many of the technical specifics in this review of process and call for aid on a final, perfect Super Nintendo emulator. But the SNES was a system that still informs my design and aesthetic sensibilities, twenty-seven years later, and I respect the author’s work very much. The most striking quote to me:

“I can tell you why this is important to me: it’s my life’s work, and I don’t want to have to say I came this close to finishing without getting the last piece of it right. I’m getting older, and I won’t be around forever. I want this final piece solved.”

What an extraordinary thing it seems, to me, to know what your life’s work is. I hope one day I do.

Again, Juvies

-

Spider-Man: Far From: Home (20:19): You can probably skip down to Yojimbo (1961), this part is a nerd trap and I’m still caught in it. Also it’s full of spoilers, if you care about that.

This purports to be a movie about the consequences of Tony Stark’s death, but even more present are the ghosts Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, who created Spider-Man together and both died in 2018. Whatever any given audience thinks of Lee, the people behind the Marvel Spider-Man movies were clearly big fans; the license plate and wrestling poster Easter eggs alone are indication of that, and the big hallucinatory illusion sequence in the second act is a big ol’ fanvid drawn straight from the Lee/Romita on-page experiments of the early 70s. I think it does Doctor Strange, another Lee/Ditko creation, better than Doctor Strange (2016) did. Sooo when you include a subplot about disgruntled people whose work was subsumed or absorbed to promote one man’s self-made aura of genius, it’s hard not to see another side of that too. There might be a movie out there that can sell me on the idea that the correspondence was deliberate, but as much as I enjoyed it, Far From Home is not that.

There’s a lot going on in the movie thematically and none of it quite gels. Is this a movie about people needing to move on? That topic keeps coming up but never gets an emotional climax. Is it a movie about how drones are bad? It’s certainly not the first Marvel film to express that unease, but why does it go unremarked that Tony Stark apparently built a global pinpoint-assassination system just like the one Steve Rogers was willing to die to destroy in The Winter Soldier (2014)? Is it a movie about whether Peter Parker—who, in current comics canon, operates a multinational tech corp in very Starkian fashion—is meant to step into his dead mentor’s role? Kind of, but that shouldn’t even be a question the MCU has to ask, because the MCU already has an established born leader and tech wunderkind for its next phase of superheroes. Their names are T’Challa and Shuri!

Is it a teen road movie? No, it backgrounds all of that in favor of very expensive-looking effects sequences. Is it a love story? Almost, almost. Tom Holland and Zendaya have about three scenes together, and they’re electric! Those two people are very good at acting! You have to have something special to actually sell me on a Peter/MJ romance in two thousand damn nineteen, and they did, but in true Sirius Black fashion, we barely get to glimpse the good stuff before it’s gone. A big flaw in the movie is how it continues the timeworn MCU tradition of failing to foreground its women; it needs not only more Zendaya, but more Cobie Smulders, and any at all of Jennifer Connelly, and more Marisa Tomei. How are you going to make a movie set in Venice with Marisa Tomei and ghost Robert Downey Junior in it and not even throw in a sly reference to Only You (1994)?

Anyway, since I started drafting this post the movie made a billion dollars, so Marvel/Columbia/Sony are probably pretty happy with Jon Watts and his directorial choices overall. I just liked Homecoming so much, and thought this showed such potential to be a movie specifically suited to my tastes, that I have a hard time not wrestling with the things it wasted and missed. NERD TRAP OVER.

-

Yojimbo (1961): Man, just look at this.

There are eight people in this shot, where one of the contenders for town boss is receiving Toshiro Mifune’s ronin and wheedling for his services. I didn’t do anything special to grab this frame—I just paused my player and took a photo of the TV with my phone, like a monster.

For the majority of people, color is a critical component of the way we separate shapes from each other, figure out what to pay attention to, and—like it or not—assess others. This image has no color dimension. But because its costume design is brilliant, my eyes immediately parse each person in the shot, and it’s even easy to grasp their ranks: the boss and his wife have the most ornate clothing, the ronin wears simple solids, and the background lieutenants each get a distinguishable but undistracting pattern. Because it’s blocked well, I know right away that Mifune is the center of the scene, with everyone else’s attitude cheated toward him. I happened to catch a frame where most of the lieutenants are looking down as they settle in, but the three principal characters always have their faces in full view or profile, so your brain can follow the conversation between them without the need to reverse between close-ups.

It’s fun to be able to break that out after the fact, and it’s even more fun to get picked up and carried along by it in motion. There’s all kinds of STUFF in Kurosawa movies: moving weather, moving fabric, bold expressions and exaggerated gestures and all kinds of people on the screen. Heck with minimalism! It’s great when the frame is busy, as long you can do it in a way that works for the viewer instead of against them. Anyway this movie is good and cool.

- The Old Man and the Gun (2018): I guess it could just be the Robert Redford fan in me speaking, but I certainly enjoyed this Robert Redford movie about movie star Robert Redford. It’s full of winks, but I was surprised to learn that casting Sissy Spacek opposite him was not one of them. They’d never been in a movie together before! They have wonderful chemistry, and I would have liked more of that instead of Casey Affleck’s dogged-mopey subplot, although his family was cute. When in doubt, always replace Casey Affleck with Sissy Spacek. Call that “the ek-eck rule.”

- Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010): This is a movie against which one critic’s epithet of “Uncle Bong Hit” can be… fairly applied. Also I really enjoyed it. The first shot in which the camera moves at all is fifty minutes in, and I’m not sure there was a single shot that lasted less than ten seconds in the whole thing; the median edit seemed somewhere around two minutes. It probably goes without saying that the only music is diegetic. Imagine those being your constraints. Imagine having that much confidence in your composition!

- Happy-Go-Lucky (2008): After talking a big game about my admiration for Sally Hawkins I decided I had to back it up by watching her breakout role, which is also my first Mike Leigh movie. Hawkins is extraordinary as expected. I knew that Leigh’s process of rehearse-improvise-rehearse-THEN write-THEN film was a whole unique thing; I did not know that the rehearsal process for this movie would have been happening while I lived in London in 2007. (I recognized zero locations aside from Hyde Park, but London is big and I lived south of the Thames.) This movie takes its time to get going, and anyone less charming than Hawkins in the lead could have grated a bit, but it’s lovely. Who else is going to make a movie that amounts to “a kind person politely and successfully asserts boundaries against hostile men, the end?”

- The Iron Monkey (1977): There are about forty movies called Iron Monkey and this is not the one directed by Yuen Woo-Ping, it’s one that was alternately titled Monkey Fist Vs. Eagle Claw and screened for the Hollywood’s monthly Kung Fu Theater night. Aside from the part where it shows a CHILD GETTING STRANGLED ON SCREEN in the first act, it’s pretty much what you’re there for.

-

Predator (1987): I love Alien (1979) and that franchise has long been a point of comparison against this one, so I decided to watch this. I didn’t like it. All right, John McTiernan, I hear your latter-day argument that this movie has some satirical intent behind it: the scene in which the bulging shout-men clear-cut an acre of rainforest using infinite bullets actually does trample right past power fantasy into grand display of impotence. It is goofy, but what does it end up saying by the end? That when the mechanized instruments of murder fail you, you must turn to… less mechanized instruments of murder? That beneath the ugly mask of sport hunting is… a face that is also ugly? I don’t buy it! This movie wants to stab its cake and shoot it too.

My favorite part was the special effects, which I think have now crossed a line from “dated” into “gloriously retro.” I spent most of the runtime thinking about the ways in which the Predator is shown to be a peerless hunter of men, to wit:

- outnumbered and outgunned at all times

- water-soluble camouflage

- glowing blood for convenient tracking

- slow-moving, light-up bullets for easy location in a firefight

- tall-ish?

- bound by strict rules of chivalry

- cannot chew food

- legally blind

- frequently sleepy

Damn, Arnold, you really skinned your teeth on that one.

-

Point Break (1991): See, with this one I can give credence to a certain archness of regard! Among Kathryn Bigelow’s other movies, I have only seen The Hurt Locker (2008), but that alone gave me reason to think she had a more nuanced understanding of masculinity than the other John McTiernan movie I have seen (Die Hard [1988]).

Contemporaneous reviews of this movie seem to have missed the homoerotic frisson that overlays the entire thing, not to mention the way the film keeps rolling its eyes at the incompetence of the FBI characters and the surfer gang’s bullshit philosophy. This is a movie shot by someone who had already watched many men’s eyes glaze over as they stopped listening because they believed they had something more important to say. The silent camera, in fact, plays with everyone here like a superior dance partner, and that’s one thing the reviews did notice—technically, the surfing and skydiving and chase sequences must have been fucking hard to shoot! There was no bullshitting with CGI in 1991, and no infinite digital storage either. For every perfect curl we get to see someone riding through in slow motion, someone else was doing the same thing, holding a camera, with a limited amount of celluloid film in a canister, backwards.

I loved this movie even though it had almost zero women in it. And having watched it, I’m now convinced that Bigelow invented the so-called Sorkin walk and talk!

- Perfect Blue (1997): It’s 1:30 in the morning and I really want to finish this roundup because it’s also almost September! This movie has sexual violence in it. It is really interesting to compare to Paprika (2006), not only for to see how far Satoshi Kon and Madhouse came as animators in ten years, but to see Kon developing what between them amounts to a career-length treatise on the Kuleshov Effect.

- High Flying Bird (2019): This movie was aaalmost ruined for me by an airbnb TV with motion smoothing turned on that I could not disable. It’s also one of two movies I watched this month that were shot on iPhones, and despite the fact that I love this cast (André Holland! Zazie Beats! Melvin Gregg from American Vandal!!) and this playwright (Tarell Alvin McCraney!!!) and of course this director, it was not the one I preferred. I enjoyed its subtle conceit about the long work of revolution, and its performances, but the decision to shoot everything in extreme wide angle with a single anamorphic lens is hard to handle. You can strap a telephoto onto an iPhone too, Steven! I really think at this point in his career that Soderbergh enjoys being able to execute what he wants very, very fast—they self-funded and shot a feature film on location in something like thirty days—and the result is not sloppy, but its spontaneity in form is a little at odds with its deliberate function.

- Tangerine (2015): See, now, this is how you shoot a movie on a phone. Grainy, artificially warm, hectic, rife with bad decisions, full of characters who see the world through this exact same lens, and fun as hell. There is homophobia in this movie and use of the n-word by white people, but it is not sexually violent, which was a relief to me. It’s on Hulu! Text me if you want my password.

Juvies

- Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping (2016): The kind of movie where you can say “so when does Justin Timberlake show up?” and “something bad is going to happen to that turtle” within the first ten minutes, and be right about both, and still have a perfectly nice time. Pretty lacking in story and screen time for women, but at least that allows for a sweet story about men needing to love each other? I guess?

- Booksmart (2019): I only discovered in the credits that the wonderful Sarah Haskins wrote this movie! She did it TEN YEARS AGO, while she was still doing Target: Women! I really, really enjoyed it—funny, genuine, sympathetic and visually nimble, with inventive sequences and a few gorgeous long shots—but that discovery made my June. I’ve never really paid much attention to Olivia Wilde, though I knew she was smart, but when you pick up a script from Sarah Haskins and do right by it, you immediately earn my loyalty. Getting Dan Nakamura to score it doesn’t hurt either.

- Always Be My Maybe (2019): It is also possible to get music from Dan Nakamura, set up interesting constraints around representation, cast people I already like, and make a movie I just can’t feel a single thing about. I think Netflix has a great opportunity to revitalize the made-for-TV movie and create a space for valuable genres (like rom-com!) that don’t always merit a theatrical release, but every time one catches my interest, the result is just so focused on being efficient and functional in hitting its marks that there’s no space for anything interesting to happen.

-

Millennium Mambo (2001): I picked this up because The Assassin (2015) made me interested in Hou Hsiao-Hsieh; I didn’t realize they both starred Shu Qi. I know film is the voyeur’s art form or whatever, but this really leans into that, I’d say even more so than something like Caché (2005). It’s like watching a play through a keyhole: the action is mostly confined to a few locations, shot with long lenses and takes that limit camera movement to little more than the occasional pivot. Sometimes there’s a table in the way of the shot, sometimes a closed door. I felt like the camera and I were both trying to lean forward and peer around the obstructions, but not in a frustrating way. It’s not just obstruction, after all—it’s bokeh and parallax, shot along long axes, just like Mackendrick liked to say. Even when you can’t see what’s happening, your eyes aren’t bored.

In terms of other movies I’ve watched this year, I was reminded of Days of Being Wild (1990), but even more so of Morvern Callar (2002)—in part for its focus on an enigmatic young woman, but also for all the rich, soft light and texture and color on the screen. I honestly don’t know if there was some kind of film stock or grading process that they have in common, but it summons the look of the early 2000s even more than the candy bar phones or club music or all the cigarettes.

I’m getting all wistful now! 2001 is the year I started this blog—please do not verify this—and I had so many ideas about the future, and no idea at all. Anyway, I am also delighted by the fact that in the second scene of this movie, one of the characters wears a shirt that just says KISS, while the other’s shirt just says ARMY.

- PlayTime (1967): The first movie I have attempted this year that has completely defeated me. I gave up halfway through, as the film entered what seemed like its third week of runtime. I am so far ahead of you on detesting modernism, Jacques Tati! I don’t need you to make lavish satire-that-is-indistinguishable-from-its-subject for two hours about it!

- Fist of Legend (1994): The second Jet Li feature in a row for for Intermittent Hong Kong Kung Fu Movie Club. This is Li and his team in their prime, working from a remake of a Bruce Lee movie, so all the pieces are in place for something solidly delightful, and it delivers: it nails color, clarity, composition and cuts, or as I call them, “four important things that start with C, and also coolness, so make it five.” I was happy that the conflict resolved from nationalist resentment (at one point Li pulls a sign reading “TOLERANCE” off a wall and punches it in half) into something more complex and forgiving.

-

Submarine (2010): I can’t believe I procrastinated on watching this for almost a decade. I love Richard Ayoade, I love Harold and Maude (1971), I love teen movies, and I like Wes Anderson a lot, so it was a foregone conclusion that I would love this. And I did. If it had just its fleet and startling pacing, or just its frank sense of humor, or just Sally Hawkins (a generational talent, an utter badass, someone who makes acting actually seem important), or even just its pinpoint costuming choices, it would be worth watching. But it has other things too! Among them, period-accurate but unnecessary homophobia, which disappointed me a bit in the midst of all this delight.

Anyway, make more movies, Richard Ayoade. I don’t want to spoil the very first frame of (the American release of) the movie for you, but it’s worth looking up.

-

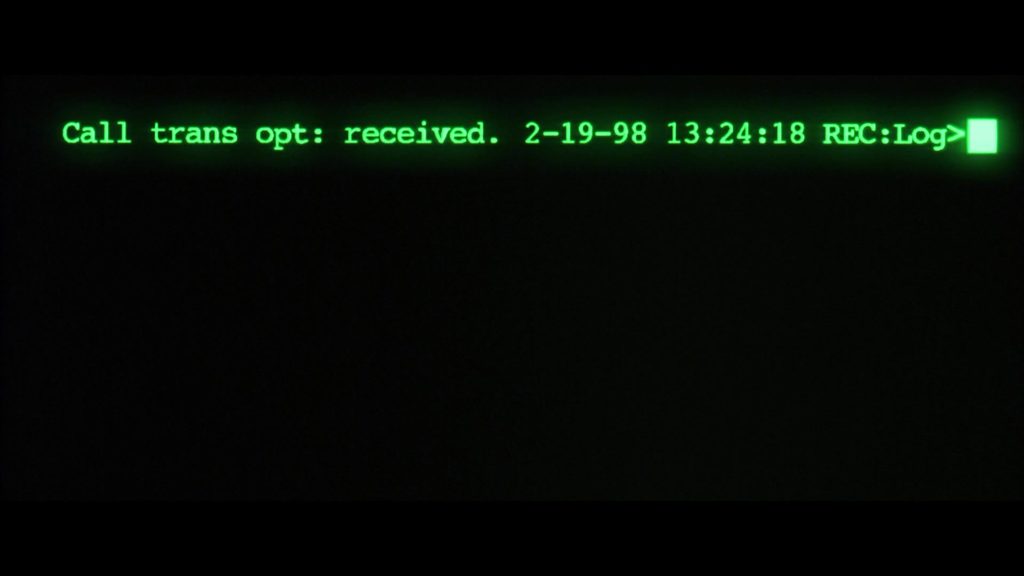

The Matrix (1999): Rewatch, of course. Man, speaking of opening frames.

Years ago, my friend Avery pointed out to me that the “red pill” isn’t just a metaphor used to promote violent misogyny after being co-opted from a woman—it’s been read as a pretty explicit allegory, in the film itself, for a hormone pill. I thought about that and found it pretty convincing as an authorial intent, especially after both the creators came out as trans, but this was the first time I’d watched the movie with that framework in mind.

And when you look for it, it’s everywhere, from the first thing you see on the screen to nearly the last. One of the first things Neo says to Trinity is “I thought you were a guy,” to which she replies “most guys do.” The character of Switch visibly presents different genders in the Matrix and the real world. The Matrix itself is described as a prison made of… binary. The Oracle tells Neo to “know thyself,” and that he’s waiting for another life. Even in the climactic fight between Neo and Smith, Smith holds Neo in front of a train he calls “inevitability” and taunts him by calling him “Mister Anderson.” Neo’s response—“my name is Neo”—isn’t just a good retort, it’s a rejection of the identity he was assigned at birth.

I have a long and complicated history of regard for The Matrix; it made a vast impression on me, but even in 1999 I could see how it seemed to me to center the experience of a generic privileged man, and how much it swiped from other creators without offering much credit. The fact that it got appropriated by self-righteous nerds and by shallow philosophy and pop culture reference gags, and that the sequels were… the sequels, didn’t help me feel great about having latched onto it myself. But this lens for it thrills me, because it takes the movie back from its worst fans and makes it vital, relevant, and still radical twenty years on. There was always something in there that was more than the sum of its parts; it just took the patient education of queer people in my life to let me see it.

- Toy Story 4 (2019): Still sweet, still technically untouchable, but pretty redundant to the story of the previous entry in the franchise, which is one of the great pre-Spiderverse creative peaks of the medium.

-

Chungking Express (1994): This is basically two short films—and was almost three—one about an oblivious young police officer blundering onward from a failed relationship while eating all the food in Hong Kong, which is followed by another about an oblivious young police officer being forced to move on from a failed relationship by a manic pixie terrifying stalker. All together I found it a little clunky, and there’s barely a thread of connection between the halves except in their themes, but the second half—the Faye Wong/Tony Leung half—is a nervous delight!

Also, the thing I linked up at the top of the previous paragraph is a video of Quentin Tarantino talking about the movie, in the comments of which I learned that Tarantino’s face accidentally introduced Barry Jenkins to this movie and to Wong’s work. There have now been two good things in comments sections on the internet.

- Black Panther (2018): Rewatch. I’m still learning from it! In one of the very last shots of the movie proper, when the basketball court has changed from night to morning, a kid walks up to T’challa to ask him who he is. As the camera drops and he steps forward, they throw a little lens flare over the top of the kid’s head. Not much! Just enough to give the shot a little flash, and timed such that they had to want it, be ready for it, and get the kid to hit his mark in the five or ten minutes where the sun was in the right place. It wouldn’t matter too much if it weren’t there. But they got it, and it is. Every time I watch this movie, it gets a little clearer just how much Ryan Coogler and Rachel Morrison and Hannah Beachler did to make this very very difficult thing look easy.

-

Bad Times at the El Royale (2018): This movie was cast well, and shot well, and designed well, and soundtracked well, and again, cast so well that it bears repeating, and I got to the end of its long runtime without any idea of what it was about. It’s a thriller without a relevant anxiety to play with, and it wants to be a noir movie, but it doesn’t really have a Thou Shalt Not with which to punish its characters. It spends minutes on end detailing the central conceit of its bi-state hotel setting, and then never actually uses that for anything. Speaking of Tarantino, it looks a lot like one of his later movies, but without any of the moments Tarantino takes to bust out into gleeful, visible artifice.

All of which is to say I wasn’t offended by this movie, and maybe I’m missing something, I just don’t know if there’s a there there. It did, however, confirm my strong parasocial relationship with Cynthia Erivo (lately of Widows [2018]), and one part that made both Kat and I yelp was spotting Manny Jacinto from The Good Place in the credits. He grew a mustache!

(Updated 0734 hrs because I forgot to insert the picture!)

Kat sent me an article that bothered me, so I wrote a post for my employer’s blog about some of my favorite hobbyhorses. (I like my job; let me know if you want to work here.)

April Roundup du Filme

If there’s one thing I should have seen staring at me in last month’s roundup, where I raved about Barry Jenkins, Wong Kar-Wai and Jordan Peele, it is that if I want to find work that is exciting and engaging to me and made by people who came out the gate really strong, I cannot rely on movies made by (straight cis) white dudes. This is hardly a new concept, but that does not make it easy to put into practice. I’m still trying.

Also, I regret to say that I didn’t watch any movies I hated this month. Sorry, Last Month Concluding Paragraph Brendan.

- Morvern Callar (2002): When people talk about women not winning the big awards for directing, they are required to mention Lynne Ramsay, and I had never seen a Lynne Ramsay movie until this one. I enjoyed it. Ramsay worked in still photography before becoming a filmmaker, and it shows: she seems to compose things so that pausing on any frame would leave you with something you could hang on a wall. Lots of grain and contrast, shallow depth of field, and a technique with two distinct levels of saturation that echoes the one in Medicine for Melancholy (2008). But Barry Jenkins used his version to catch the heart right out of you, or try to; Lynne Ramsay uses it here to keep you on the outside surface of her pretty enigma.

- The Third Man (1949): I had to watch this if I wanted to keep studying Alexander Mackendrick, because he really loved its plot and structure. It’s a classic and its structure is interesting: all its characters are dynamic, doing the “active in their own narrative” thing that is so fun to notice within all kinds of stories, so the whole movie functions a bit like an orrery. It has cool shots too, and I enjoyed it—I see why it’s a great teaching example. But even as someone who doesn’t know a ton about Orson Welles, it seems clear to me that it wouldn’t exist without him! It’s a satellite, in the well of his gravity not only as a filmmaker but as an actor. He has a middling amount of screen time, but only one speaking scene, and it’s the most memorable element of the movie. He compels. The rumors about him shadow-directing the movie were a myth, but he didn’t have to direct it or even be on set most of the time to shape the whole thing.

-

Get Out (2017): It’s Auteur Month on the Roundup du Filme!! It’s not actually Auteur Month on the Roundup du Filme. My understanding of this movie from its first trailer up until last month was that it would jab directly into the areas that are hardest for me to bear in fiction; I only decided I was brave enough to watch it after I survived Us (2019) without losing my mind. One cool thing I noticed seemed like a twist on a thing I referenced back in January.

In Night of the Living Dead (1968), as required by its chief technical constraint, the scenes of respite and interpersonal conflict are all shot on a tripod; it was the only way to hold the camera while recording sound. When shit goes down with the zombies, the music swells and the camera goes handheld, emphasizing the chaos with the shaking frame. Many, many people have relied on that jitter-means-jittery technique ever since. In Get Out (2017), the opening and all the interpersonal stuff is shot handheld—not shaky, but not steady either. That takes advantage of the other implication of handheld shots, which is intimacy within emotional relationships. It’s only when you’re watching something that foreshadows or explicates the movie’s horrors that you get a smooth dolly or a static frame, and many of those are wide shots from a distance. Instead of chaos up close, you get dread at a helpless remove, which (SPOILERS) ties into the protagonist’s experience. I don’t know if Peele was the first to do that flip, but he does it well.

- A New Leaf (1971): There’s a well-known filmmaker who has made a lot of comedies about himself as a series of similar nebbishy characters. I’ve seen a few of his movies and had never seen any of Elaine May’s. This movie orbits around a nebbishy character, played by its writer-director, so that’s where my mind went as a point of comparison, but it’s a lot more ambitious than that as a formal exercise alone: it’s a romantic comedy trying to squeeze into a Wodehose farce, but it’s set in the 70s, but it’s really about the nakedness of class warfare, to a murderous point. I didn’t realize this was her first feature! The performances she elicited were my favorite part—I’d never seen this side of Walter Matthau, for instance. I did get a sense that something about the plot steered a little away from its really wicked impulses, and I think it turns out that what I really wanted was to see that three-hour director’s cut.

- The Ladykillers (1955): Alexander Mackendrick again. I’d seen the Coens’ remake but not the original, which is a very different movie. I think this one is a bit less mean-spirited, and kind of a light dark comedy. Like A New Leaf (1971)! (They also both do this funny thing with rear-projection insert shots, the CGI backgrounds of 1940-1980.) Technically delightful, just like the other movies of his I’ve seen: it carries and guides your gaze and your sense of tension with assurance through the whole movie. Putting Alec Guinness in goofy dentures and flop-sweat hair is a great move, because it lets him cut loose in a way I’d never seen anywhere else. Having seen him really commit in a role makes Star Wars seem very strange by comparison!

- Raising Arizona (1987): Speaking of the Coens, this is the earliest of their movies I’ve seen. I don’t remember where I read about it as a Looney Tunes homage, but man, it’s not hiding that at all! I enjoyed that aspect, and seeing this phase in their development: it sits well within the bounds of the strict “one freaking time” universe, but because these are cartoon characters, they are more resilient against its consequences than humans. Also, this might be the first Coen movie I’ve seen that doesn’t commit to their signature anticlimax, although it’s been a while since I saw Miller’s Crossing (1990).

- Someone Great (2019): A Netflix trifle. Written and directed by the same person, and I feel like it’s kind of unusual that the directing seemed much stronger than the script? Like, the long takes are understated but very effective, and the fake cross-processed lighting in the flashbacks is a treat. The flashbacks are the best part of the movie, in fact, even though it’s supposed to really be about friendships among women—Lakeith Stanfield and Gina Rodriguez, for whom I have strong parasocial affection, have great chemistry despite some pretty weak lines. This is the kind of movie that names itself after a song, doesn’t understand that song, and doesn’t actually have the song on its soundtrack because it can’t get clearance. But somebody spent a million bucks and tossed it out there anyway. Netflix, everybody!

- The History Boys (2006): Kat’s favorite; I was entranced by it. It’s an adaptation of a stage play featuring its original cast, and it sounds like a stage play featuring its original cast, in that its lines are longer and a little more florid than you expect from a screenplay and also one of the actors playing a high schooler is clearly 28. It won a lot of awards and got made into a movie for a reason, though. This is a very affecting movie about sexuality and about sexual abuse. It treats both of them with equal tenderness, which is… complicated, as moral stances go. But the cast is really stacked with character-actor ringers, and it doesn’t look stagey at all.

- Empire Records (1995): Rewatch for Rex Manning Day. This movie also has a tricky moral stance, advocating as it does for Nice Guys and the primacy of physical music media. It lacks the courage to convict itself and its treatment of its female characters is kind of cringey. But a nineties movie can fail in a lot of ways and still have bits in it that render themselves indelible in one’s mind.

- Avengers: Endgame (2019): My favorite of the Avengers movies so far, even though—like its predecessors and like all popcorn—it was delightful while fresh and then aged quickly as it cooled. I was well served by the fanservice, but Caroline Siede is correct to note that it treats some heroes as more equal than others. That said, the Russos did their best to pay off all the setup I deplored in Infinity War, and a lot of other setup going back a long way, and their reward was that they got to break many of the restrictions that held the previous Avengers movies down.

-

Homecoming (2019): Okay, maybe it is actually Auteur Month on the Roundup du Filme. I’ve seen Beyoncé in concert, on the Formation tour in St. Louis in 2016, and it was a tremendous experience. For someone who does not have a background as a composer, a writer, a designer or a cinematographer to demonstrate her level of specific creative control is interesting; this concert doc is styled “A Film By Beyoncé” and I don’t think it’s just puffery.

The popular discourse goes like this: 1) “you have as many hours in the day as Beyoncé,” 2) “no, Beyoncé’s wealth grants her time via the labor of others.” The thing is, though, even if I had all her resources, I am certain that I would not have her reserves of will. The parts of this movie that document the work of creation leading up to the performance make that clear. She was in a rehearsal space hashing out the initial concepts of the show within two months of giving birth, to twins, and the work of expansion and refinement continued right up to the opening performance, plus the following week until its closing one. I have no illusions that I want to hang out with Beyoncé. But while I do not believe in the divine right of royalty, sometimes I understand why people did.

January Movie Roundup

January Film Roundup is the intellectual property of Leonard Richardson and Nowhere Standard Inc. Any resemblance to actual film roundups living or dead is purely incidental.

A thing I did in 2017 that I’ve never actually recorded here was buy a house in Southeast Portland. More about that some other time. An important thing about this house, to me, is that it’s within walking distance of Movie Madness, the best place to rent movies in the world. Later in 2019 I’m going to leave Portland after eleven years and move to Chicago. More about that also some other time. Until then, I want to take great advantage of my proximity to the little cinder block building that just has… every… movie… in it. These are the ones I watched last month.

-

My Best Friend’s Wedding (1997): Kat’s favorite. I used to watch and basically believe in romantic comedies, a fact which may shed light on some of my permanent emotional scarring. I stopped watching in the early oughts, when the movies stopped being good, but I think I did see almost all of the nineties classics except this one. I liked it but I’m glad I didn’t see it at the time; I would not have appreciated it.

Having read nothing about its production, here’s my imaginary series of events: Ron Bass sees Mr. Wrong and The Truth About Cats And Dogs in 1996, then writes a combination of the two as a vehicle for Janeane Garofalo or someone Janeane Garofalesque. A studio buyer says “Ron, I love it, but why don’t we see if we can shoot for someone more… Julia Robertsesque.” Then the actual Julia Roberts, tired of being pitched on romantic comedies because it’s 1997, reads it and says “I would enjoy taking my own subversive turn at playing a sociopath,” and what you end up with is this strange world where Dermot Mulroney plays a human tree stump who’s marrying 20-year-old Cameron Diaz yet who has never in his life considered any attraction to Julia Roberts (who is in turn willing to ruin his life to have him).

I grant you that this is the same disbelief you are asked to suspend when The Truth About Cats And Dogs sets up its false dichotomy, but at least that is predictable Hollywood logic at work. Roberts gets her teeth into this anyway and has a great time, which is fun to watch, and so does Rupert Everett, who you already know is the best part of the movie even if you’ve never seen it.

-

Night of the Living Dead (1968): I think I saw this nineteen or twenty years ago and my recall of it was more accurate than I expected. I like it, but I would not have felt a specific need to rent it except for one thing: I seem to be among few Every Frame a Painting superfans to have discovered that last year’s Criterion reissue has a hidden Every Frame a Painting on the bonus disc.

To say that Every Frame a Painting meant a great deal to me is to understate. It turns out I am still grieving it, and—as is obvious to the point of pain—grieving the world I thought I was living in when its last video was posted to Youtube in September of 2016. Grief leads me to magical thinking, and so, of late, my brain has tried to conjure the past via whatever ancillary frames I can find. There are at least a couple more essays they produced for Filmstruck, a service which decided to shut down just as this bout of grief made itself known, that I haven’t found yet. But I have found three others (on The Breaking Point, His Girl Friday and Tampopo) in physical format at Movie Madness.

-

A Taxing Woman (1987): I enjoyed Tampopo so goddamn much that my friend Theron recommended I try to track this one down, the movie Juzo Itami made after it with the same leads. Even Theron had only ever seen this on VHS, but Movie Madness had it on DVD, because they have… every… movie. Tampopo is somehow a Western about cooking noodles, so of course this one is a gumshoe tax fraud noir in a world where everyone is constantly trying to cheat on their taxes. The genre twist I liked is that this time the detective character is on the offense: she’s the one who barges into other people’s offices, smelling like trouble. It’s fun just to see Nobuko Miyamoto and Tsutomu Yamazaki stretch their rapport into something wary and oppositional instead of bittersweetly pedagogical.

-

The Bad Sleep Well (1960): Three out of four of this month’s movies are directly derived from Every Frame a Painting, a trend which I expect will continue. This one got its own mini-episode about one scene—actually, about one shot—and I successfully used that to walk myself backwards into watching my first Kurosawa movie in decades. I enjoyed it.

I used to get bored very quickly by any movie I perceived as “old.” The only way I knew how to interpret film was through plots, which I tended to find either obvious or incomprehensible in the classics, their dialogue, which I found unrelatable, and their set pieces or action scenes, which I mostly found cheesy. Yes, this is callow, but I don’t think it’s uncommon! I could write at length about how standard liberal arts curricula can fail people, but fundamentally, putting complex art in front of someone and declaring that it’s valuable by fiat doesn’t work. I have seen so many movies without knowing how to see them. Modernist artistic complexity is a locked door with treasure behind it, but if the keys you have for the door don’t open it, the fault is not with you.

Every Frame a Painting showed me doors I didn’t know about, and nudged them open for me. I notice when my eyes are active in the frame now! I can identify different kinds of cuts between shots, and I notice when the camera directs my attention amid complex blocking. I can appreciate it when action and reaction are both in the same shot, or when one shot just set me up for its successor. I haven’t quite managed to catch compositional sectioning in action yet, but at least I know it’s out there to be recognized.

Each of the previous Kurosawa movies I’d seen (Ran, Throne of Blood, Rashomon, The Hidden Fortress and Seven Samurai) were things I found nebulously cool and even striking, but like Michael Bay, I couldn’t have articulated why. With The Bad Sleep Well, I can tell you this much: I like it because it doesn’t matter whether I speak Japanese or whether I speak cinematic shorthand (or whether I know Hamlet). I like it because it told me a harmonic story with its acting, its writing, its music, its composition, its costuming—in monochrome!—and its editing all at the same time. It uses its bandwidth well in concert, and a broader band means richer media.

I also liked it because Toshiro Mifune is nebulously cool.

It took me a while to hash that last point out with myself, so now it’s February 5th and I’ve already seen three more movies and rented a fourth. I guess we’ll see how long this keeps going, and also how many choices of movie I can tie back to Every Frame a Painting somehow. Maybe Leonard will forgive this format infringement if I tell him that I am about to finally get around to watching The Man Who Wasn’t There.

General Clap

Hey, I finally discovered that back in May I placed in the 2018 Lyttle Lytton contest! Specifically I placed with an entry in the Found division—just scroll down to where my name is spelled wrong. I am proud even though it’s not like I wrote anything for it. But the reason the biggest category on this old blog is called “connections” is that I still delight in plugging one thing (a bad sentence I read) into another thing (a web site I love).

And there are a lot of connections that really worked for me in this year’s list! It’s good company to be in. Not only did another Found winner pull an egregious bit from my most hated episode of one of my all-time favorite shows, but there’s an entry under the Perennials that recalls my first entry. There are bullet journal and Engagement Chicken jokes too (hi Kat). But the thing that really rang my bell was seeing a semi-vanished webcomic writer—someone I still admire—pop in with a brilliant entry, and Adam Cadre give her a wink and a nod. I don’t chase the Internet as hard as I used to, but I’m glad the cool-kid serendipity of a decade ago isn’t all gone.