- Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping (2016): The kind of movie where you can say “so when does Justin Timberlake show up?” and “something bad is going to happen to that turtle” within the first ten minutes, and be right about both, and still have a perfectly nice time. Pretty lacking in story and screen time for women, but at least that allows for a sweet story about men needing to love each other? I guess?

- Booksmart (2019): I only discovered in the credits that the wonderful Sarah Haskins wrote this movie! She did it TEN YEARS AGO, while she was still doing Target: Women! I really, really enjoyed it—funny, genuine, sympathetic and visually nimble, with inventive sequences and a few gorgeous long shots—but that discovery made my June. I’ve never really paid much attention to Olivia Wilde, though I knew she was smart, but when you pick up a script from Sarah Haskins and do right by it, you immediately earn my loyalty. Getting Dan Nakamura to score it doesn’t hurt either.

- Always Be My Maybe (2019): It is also possible to get music from Dan Nakamura, set up interesting constraints around representation, cast people I already like, and make a movie I just can’t feel a single thing about. I think Netflix has a great opportunity to revitalize the made-for-TV movie and create a space for valuable genres (like rom-com!) that don’t always merit a theatrical release, but every time one catches my interest, the result is just so focused on being efficient and functional in hitting its marks that there’s no space for anything interesting to happen.

-

Millennium Mambo (2001): I picked this up because The Assassin (2015) made me interested in Hou Hsiao-Hsieh; I didn’t realize they both starred Shu Qi. I know film is the voyeur’s art form or whatever, but this really leans into that, I’d say even more so than something like Caché (2005). It’s like watching a play through a keyhole: the action is mostly confined to a few locations, shot with long lenses and takes that limit camera movement to little more than the occasional pivot. Sometimes there’s a table in the way of the shot, sometimes a closed door. I felt like the camera and I were both trying to lean forward and peer around the obstructions, but not in a frustrating way. It’s not just obstruction, after all—it’s bokeh and parallax, shot along long axes, just like Mackendrick liked to say. Even when you can’t see what’s happening, your eyes aren’t bored.

In terms of other movies I’ve watched this year, I was reminded of Days of Being Wild (1990), but even more so of Morvern Callar (2002)—in part for its focus on an enigmatic young woman, but also for all the rich, soft light and texture and color on the screen. I honestly don’t know if there was some kind of film stock or grading process that they have in common, but it summons the look of the early 2000s even more than the candy bar phones or club music or all the cigarettes.

I’m getting all wistful now! 2001 is the year I started this blog—please do not verify this—and I had so many ideas about the future, and no idea at all. Anyway, I am also delighted by the fact that in the second scene of this movie, one of the characters wears a shirt that just says KISS, while the other’s shirt just says ARMY.

- PlayTime (1967): The first movie I have attempted this year that has completely defeated me. I gave up halfway through, as the film entered what seemed like its third week of runtime. I am so far ahead of you on detesting modernism, Jacques Tati! I don’t need you to make lavish satire-that-is-indistinguishable-from-its-subject for two hours about it!

- Fist of Legend (1994): The second Jet Li feature in a row for for Intermittent Hong Kong Kung Fu Movie Club. This is Li and his team in their prime, working from a remake of a Bruce Lee movie, so all the pieces are in place for something solidly delightful, and it delivers: it nails color, clarity, composition and cuts, or as I call them, “four important things that start with C, and also coolness, so make it five.” I was happy that the conflict resolved from nationalist resentment (at one point Li pulls a sign reading “TOLERANCE” off a wall and punches it in half) into something more complex and forgiving.

-

Submarine (2010): I can’t believe I procrastinated on watching this for almost a decade. I love Richard Ayoade, I love Harold and Maude (1971), I love teen movies, and I like Wes Anderson a lot, so it was a foregone conclusion that I would love this. And I did. If it had just its fleet and startling pacing, or just its frank sense of humor, or just Sally Hawkins (a generational talent, an utter badass, someone who makes acting actually seem important), or even just its pinpoint costuming choices, it would be worth watching. But it has other things too! Among them, period-accurate but unnecessary homophobia, which disappointed me a bit in the midst of all this delight.

Anyway, make more movies, Richard Ayoade. I don’t want to spoil the very first frame of (the American release of) the movie for you, but it’s worth looking up.

-

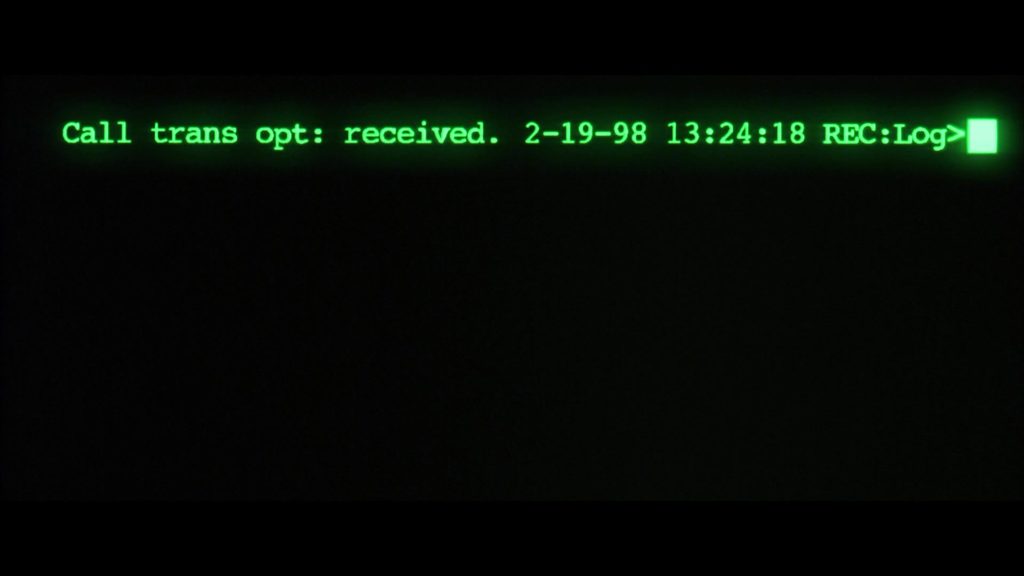

The Matrix (1999): Rewatch, of course. Man, speaking of opening frames.

Years ago, my friend Avery pointed out to me that the “red pill” isn’t just a metaphor used to promote violent misogyny after being co-opted from a woman—it’s been read as a pretty explicit allegory, in the film itself, for a hormone pill. I thought about that and found it pretty convincing as an authorial intent, especially after both the creators came out as trans, but this was the first time I’d watched the movie with that framework in mind.

And when you look for it, it’s everywhere, from the first thing you see on the screen to nearly the last. One of the first things Neo says to Trinity is “I thought you were a guy,” to which she replies “most guys do.” The character of Switch visibly presents different genders in the Matrix and the real world. The Matrix itself is described as a prison made of… binary. The Oracle tells Neo to “know thyself,” and that he’s waiting for another life. Even in the climactic fight between Neo and Smith, Smith holds Neo in front of a train he calls “inevitability” and taunts him by calling him “Mister Anderson.” Neo’s response—“my name is Neo”—isn’t just a good retort, it’s a rejection of the identity he was assigned at birth.

I have a long and complicated history of regard for The Matrix; it made a vast impression on me, but even in 1999 I could see how it seemed to me to center the experience of a generic privileged man, and how much it swiped from other creators without offering much credit. The fact that it got appropriated by self-righteous nerds and by shallow philosophy and pop culture reference gags, and that the sequels were… the sequels, didn’t help me feel great about having latched onto it myself. But this lens for it thrills me, because it takes the movie back from its worst fans and makes it vital, relevant, and still radical twenty years on. There was always something in there that was more than the sum of its parts; it just took the patient education of queer people in my life to let me see it.

- Toy Story 4 (2019): Still sweet, still technically untouchable, but pretty redundant to the story of the previous entry in the franchise, which is one of the great pre-Spiderverse creative peaks of the medium.

-

Chungking Express (1994): This is basically two short films—and was almost three—one about an oblivious young police officer blundering onward from a failed relationship while eating all the food in Hong Kong, which is followed by another about an oblivious young police officer being forced to move on from a failed relationship by a manic pixie terrifying stalker. All together I found it a little clunky, and there’s barely a thread of connection between the halves except in their themes, but the second half—the Faye Wong/Tony Leung half—is a nervous delight!

Also, the thing I linked up at the top of the previous paragraph is a video of Quentin Tarantino talking about the movie, in the comments of which I learned that Tarantino’s face accidentally introduced Barry Jenkins to this movie and to Wong’s work. There have now been two good things in comments sections on the internet.

- Black Panther (2018): Rewatch. I’m still learning from it! In one of the very last shots of the movie proper, when the basketball court has changed from night to morning, a kid walks up to T’challa to ask him who he is. As the camera drops and he steps forward, they throw a little lens flare over the top of the kid’s head. Not much! Just enough to give the shot a little flash, and timed such that they had to want it, be ready for it, and get the kid to hit his mark in the five or ten minutes where the sun was in the right place. It wouldn’t matter too much if it weren’t there. But they got it, and it is. Every time I watch this movie, it gets a little clearer just how much Ryan Coogler and Rachel Morrison and Hannah Beachler did to make this very very difficult thing look easy.

-

Bad Times at the El Royale (2018): This movie was cast well, and shot well, and designed well, and soundtracked well, and again, cast so well that it bears repeating, and I got to the end of its long runtime without any idea of what it was about. It’s a thriller without a relevant anxiety to play with, and it wants to be a noir movie, but it doesn’t really have a Thou Shalt Not with which to punish its characters. It spends minutes on end detailing the central conceit of its bi-state hotel setting, and then never actually uses that for anything. Speaking of Tarantino, it looks a lot like one of his later movies, but without any of the moments Tarantino takes to bust out into gleeful, visible artifice.

All of which is to say I wasn’t offended by this movie, and maybe I’m missing something, I just don’t know if there’s a there there. It did, however, confirm my strong parasocial relationship with Cynthia Erivo (lately of Widows [2018]), and one part that made both Kat and I yelp was spotting Manny Jacinto from The Good Place in the credits. He grew a mustache!

(Updated 0734 hrs because I forgot to insert the picture!)