Nineteen years ago my friends got together, led by Maria (hi Maria), and chipped in to buy me my first single-lens reflex camera: a Canon Digital Rebel.

I’d played with cameras since I was a kid, but until that year, I never had a solid understanding of what to do with them. Coming to that understanding took many years of developing taste for what I liked in pictures, and then more time studying the techniques involved, but mostly what I needed was a good way to experiment. My goofy webcam selfies aside, the time between taking a photo and looking at it had always been measured in weeks and dollars. But things changed once I could just snap, and chimp, and gauge what I had wanted against what I got. I needed feedback to learn.

I’d played with cameras since I was a kid, but until that year, I never had a solid understanding of what to do with them. Coming to that understanding took many years of developing taste for what I liked in pictures, and then more time studying the techniques involved, but mostly what I needed was a good way to experiment. My goofy webcam selfies aside, the time between taking a photo and looking at it had always been measured in weeks and dollars. But things changed once I could just snap, and chimp, and gauge what I had wanted against what I got. I needed feedback to learn.

I’ve written about this in the past and I don’t want to keep retelling the same stories. But before I had a camera in my hand, I had no patience for the act of looking around me. It was only learning how to frame, evaluate light, and search for details to isolate that unlocked the pleasure of observation. After a while, I didn’t even need the camera to enjoy it! And now I prefer to shoot on film anyway, so the quick feedback loop is long gone. But the process of learning shaped me, and I still hold that shape.

I’ve written about this in the past and I don’t want to keep retelling the same stories. But before I had a camera in my hand, I had no patience for the act of looking around me. It was only learning how to frame, evaluate light, and search for details to isolate that unlocked the pleasure of observation. After a while, I didn’t even need the camera to enjoy it! And now I prefer to shoot on film anyway, so the quick feedback loop is long gone. But the process of learning shaped me, and I still hold that shape.

Photography changed my world by making any moment, anywhere, into something I could interact with. You should email a blogger today.

Photography changed my world by making any moment, anywhere, into something I could interact with. You should email a blogger today.

“It’s quite important to know that you are heard.”

Jenny’s post about metrics (and Lucy’s quotation of it) have been rattling around in my head for months now. In my mind that post links back to something that Avery Alder said on twitter many, many years ago, in response to a wave of scolding directed at allies who purportedly “wanted a cookie” for taking part in social justice activism. I can no longer access the original wording. What I recall is that Avery acknowledged that of course such work is worth doing regardless of reward. And then she added: but so what if I still want a cookie? I like cookies!

Jenny again, deliberately out of context, because it fits other contexts too:

First of all, so? And second of all, right, exactly.

I like cookies too. And I’m a human, a social mammal whose development rests largely on the attention and response of other members of my species. It is important for humans that sometimes someone gives you a cookie. It is important to know that you are heard.

Analytics software offers numbers you can’t trust about visits you can’t see, which is not the same as being heard—in fact I think it might be the opposite. The illusion of attention contorts people into shapes that are not good for them. (I don’t even need to mention any prominent software platforms by name here, do I?)

I don’t use my degree in the dramatic arts for all that much, these days, but I am often grateful for what I learned in completing it. One of the things that Patrick Kagan-Moore said to me, the night before our play debuted, has stuck with me for 25 years. “We rehearse for months,” he said, “so we can try to find the right shape for the performance, and the first time you get a laugh from a crowd—” He snapped his fingers. “—they will train you, like that. You’ll do it the exact same way every show, trying to get that to happen again.”

Live performance is a hot medium, where response arrives quickly: snap, chimp, gauge. Writing online, and off social media, is a cold medium. That’s why the warmth of a good response matters so much.

Sometimes I like to reach into my mental pocket and offer up chestnuts—I know I already used one food metaphor, stay with me—which I cannot promise will contain any meat. One such chestnut is that email is the infrastructure of the web. (In my grouchier moments, I say “failure state” instead.)

Infrastructure is what you fall back onto when a superstructure cannot support the load placed upon it. There are a million diagrams of the technical stack that underlies HTTP, and none of them includes a layer called “email.” But it is there, invisible, at the root of every auth request. And as direct communication over the web has been captured by those who do not wish good things for you or me, email remains the fallback there too: a crummy foundation that yet resists collapse.

When the web promised that you could subscribe directly to the words and work of people you found interesting, then broke that promise for extractive purposes, email newsletters sprang up to fit the popular demand to Just See The Goddamn People You Follow In Chronological Order God Dammit. Email is not well fit for this purpose, any more than it is for supporting the rest of the internet. The things you want to savor from your favorite writers get buried among “the to-do list that grows without your consent” (credit to Sumana). But it kind of works. And things that kind of work are what we have, online, these days.

Newsletters are blogs. Email kind of works as a way of both delivering and responding to blogs. I agree with Erin’s newsletter that writing letters is a wonderful practice too. And I don’t mean to dismiss the charm of a good comment, for blogs with comments! Comments are how I met Will, after all. But letters require physical acquaintance, and comments are a kind of public performance in their own right. Email is something else still.

The other day I had a question that was bugging me, and I looked up the relevant figure on Wikipedia. Wikipedia told me that he has a blog—a delightful blog about sailing in retirement, unrelated to the matter I had in mind. But that blog had an about page with an email address, so I wrote an email, and got a response right away.

From: Brendan (xorph@xorph.com)

To: ken@kensblog.com

Hello Mr. Williams! I’ve always wondered, why did you choose “on-line” for the original company name “On-Line Systems?” Was it derived from the idea of making software to be accessed on a mainframe through a terminal, or did the term mean something different to you at the time?

Thanks! Hope your seagoing adventures this year are wonderful.

—Brendan J

From: Ken Williams (ken@kensblog.com)

To: Brendan

You nailed it. Yes – I was doing freelance contract work on mainframe computers, specializing in large computer networks (literally on-line systems). When I started Sierra I kept the name I had been using for my contracting.

When we started getting larger I realized someone already owned the name and had to change our company name.

-Ken W

From: Brendan (xorph@xorph.com)

To: ken@kensblog.com

It’s so satisfying to have a clear answer to that after all these years. Thank you so much!

From: Ken Williams (ken@kensblog.com)

To: Brendan

🙂👍

The exchange was months ago, but I continue to enjoy the pleasant feeling of this tiny conversation. I have other emails I have received in years past that I keep close in my heart, just because they caught me at a good moment with a kind word. Even without much social media in my life, I do talk to people in other ways online, via Izzzzi and Peach and sometimes (sigh) Discord. But a few lines of thoughtful outreach, one to one, carry a warmth and weight of meaning that is singular.

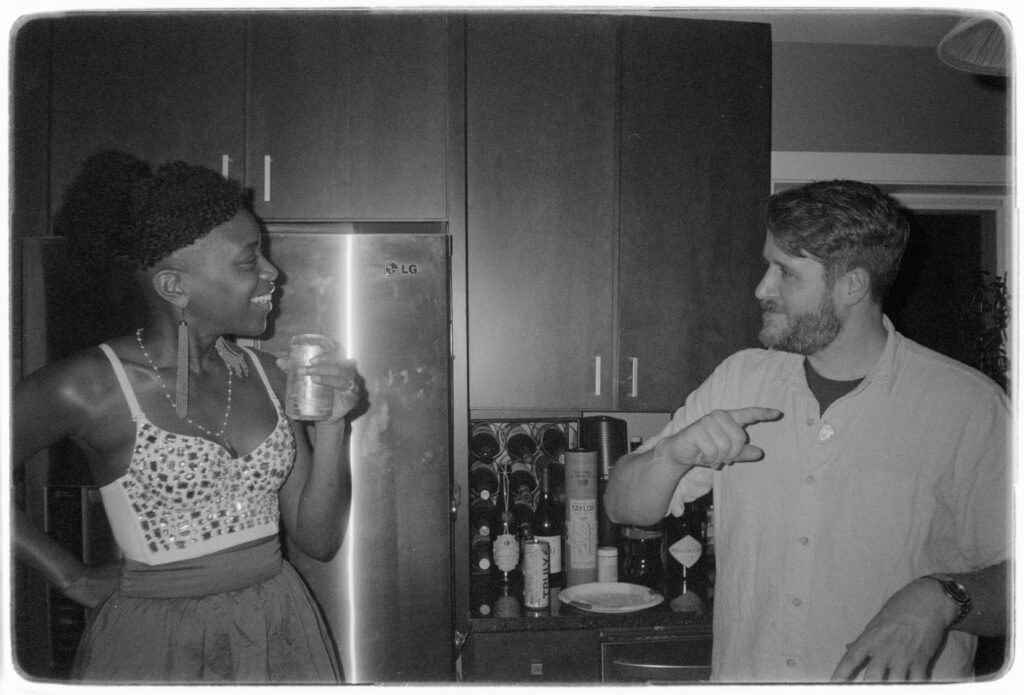

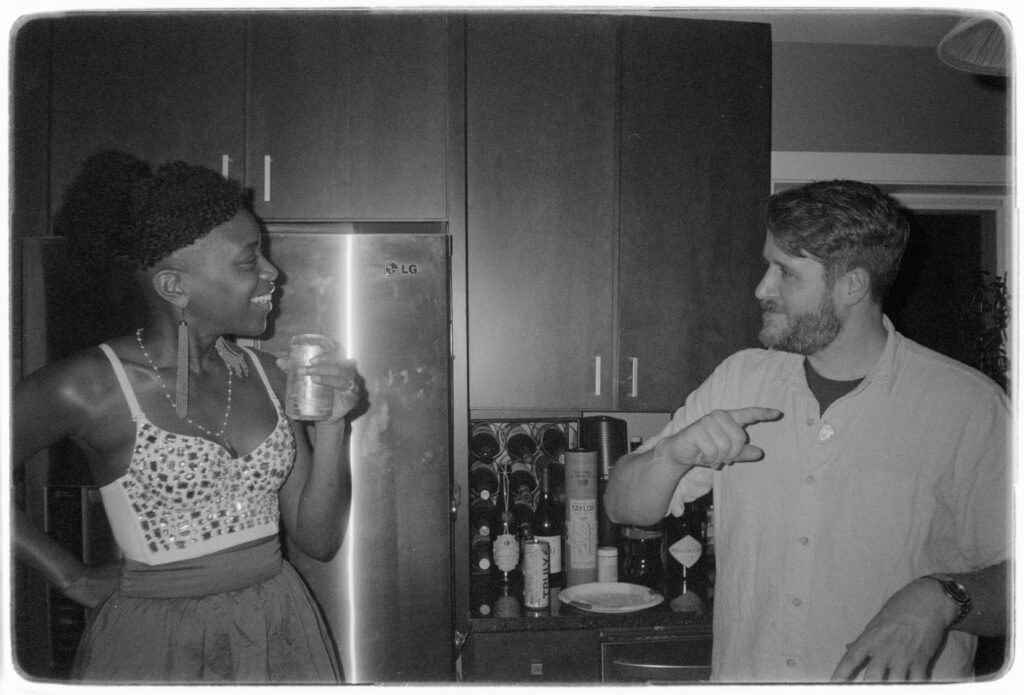

I’ve taken a lot of photos over the last couple of decades. In doing so I have learned that I’m not particularly adept in most genres. Landscape and street photography don’t come naturally to me, posed portraiture remains elusive, and things like sports or wildlife photography are far beyond my abilities. What I like shooting most are candids. They require at least a little skill, a little preparation, a watchful eye, and luck: I shoot a dozen for every picture that turns out the way I want it. But there is nothing like that moment of resolution, when I see on a screen that taking the shot has succeeded.

A photo doesn’t really make a moment permanent. Our photos are ephemeral, just like our selves. They still matter. Ephemeral connections, one to one, are the material we use to construct meaning in our own stories. You and I were born in a time when there is no other choice but to find our lives shaped by emails. So pick a shape you like, and put something in it that you want to see again.