“These limitations come with pros and cons… as usual.”

Category: Photography

Composition

Nineteen years ago my friends got together, led by Maria (hi Maria), and chipped in to buy me my first single-lens reflex camera: a Canon Digital Rebel.

I’d played with cameras since I was a kid, but until that year, I never had a solid understanding of what to do with them. Coming to that understanding took many years of developing taste for what I liked in pictures, and then more time studying the techniques involved, but mostly what I needed was a good way to experiment. My goofy webcam selfies aside, the time between taking a photo and looking at it had always been measured in weeks and dollars. But things changed once I could just snap, and chimp, and gauge what I had wanted against what I got. I needed feedback to learn.

I’d played with cameras since I was a kid, but until that year, I never had a solid understanding of what to do with them. Coming to that understanding took many years of developing taste for what I liked in pictures, and then more time studying the techniques involved, but mostly what I needed was a good way to experiment. My goofy webcam selfies aside, the time between taking a photo and looking at it had always been measured in weeks and dollars. But things changed once I could just snap, and chimp, and gauge what I had wanted against what I got. I needed feedback to learn.

I’ve written about this in the past and I don’t want to keep retelling the same stories. But before I had a camera in my hand, I had no patience for the act of looking around me. It was only learning how to frame, evaluate light, and search for details to isolate that unlocked the pleasure of observation. After a while, I didn’t even need the camera to enjoy it! And now I prefer to shoot on film anyway, so the quick feedback loop is long gone. But the process of learning shaped me, and I still hold that shape.

I’ve written about this in the past and I don’t want to keep retelling the same stories. But before I had a camera in my hand, I had no patience for the act of looking around me. It was only learning how to frame, evaluate light, and search for details to isolate that unlocked the pleasure of observation. After a while, I didn’t even need the camera to enjoy it! And now I prefer to shoot on film anyway, so the quick feedback loop is long gone. But the process of learning shaped me, and I still hold that shape.

Photography changed my world by making any moment, anywhere, into something I could interact with. You should email a blogger today.

Photography changed my world by making any moment, anywhere, into something I could interact with. You should email a blogger today.

“It’s quite important to know that you are heard.”

Jenny’s post about metrics (and Lucy’s quotation of it) have been rattling around in my head for months now. In my mind that post links back to something that Avery Alder said on twitter many, many years ago, in response to a wave of scolding directed at allies who purportedly “wanted a cookie” for taking part in social justice activism. I can no longer access the original wording. What I recall is that Avery acknowledged that of course such work is worth doing regardless of reward. And then she added: but so what if I still want a cookie? I like cookies!

Jenny again, deliberately out of context, because it fits other contexts too:

First of all, so? And second of all, right, exactly.

I like cookies too. And I’m a human, a social mammal whose development rests largely on the attention and response of other members of my species. It is important for humans that sometimes someone gives you a cookie. It is important to know that you are heard.

Analytics software offers numbers you can’t trust about visits you can’t see, which is not the same as being heard—in fact I think it might be the opposite. The illusion of attention contorts people into shapes that are not good for them. (I don’t even need to mention any prominent software platforms by name here, do I?)

I don’t use my degree in the dramatic arts for all that much, these days, but I am often grateful for what I learned in completing it. One of the things that Patrick Kagan-Moore said to me, the night before our play debuted, has stuck with me for 25 years. “We rehearse for months,” he said, “so we can try to find the right shape for the performance, and the first time you get a laugh from a crowd—” He snapped his fingers. “—they will train you, like that. You’ll do it the exact same way every show, trying to get that to happen again.”

Live performance is a hot medium, where response arrives quickly: snap, chimp, gauge. Writing online, and off social media, is a cold medium. That’s why the warmth of a good response matters so much.

Sometimes I like to reach into my mental pocket and offer up chestnuts—I know I already used one food metaphor, stay with me—which I cannot promise will contain any meat. One such chestnut is that email is the infrastructure of the web. (In my grouchier moments, I say “failure state” instead.)

Infrastructure is what you fall back onto when a superstructure cannot support the load placed upon it. There are a million diagrams of the technical stack that underlies HTTP, and none of them includes a layer called “email.” But it is there, invisible, at the root of every auth request. And as direct communication over the web has been captured by those who do not wish good things for you or me, email remains the fallback there too: a crummy foundation that yet resists collapse.

When the web promised that you could subscribe directly to the words and work of people you found interesting, then broke that promise for extractive purposes, email newsletters sprang up to fit the popular demand to Just See The Goddamn People You Follow In Chronological Order God Dammit. Email is not well fit for this purpose, any more than it is for supporting the rest of the internet. The things you want to savor from your favorite writers get buried among “the to-do list that grows without your consent” (credit to Sumana). But it kind of works. And things that kind of work are what we have, online, these days.

Newsletters are blogs. Email kind of works as a way of both delivering and responding to blogs. I agree with Erin’s newsletter that writing letters is a wonderful practice too. And I don’t mean to dismiss the charm of a good comment, for blogs with comments! Comments are how I met Will, after all. But letters require physical acquaintance, and comments are a kind of public performance in their own right. Email is something else still.

The other day I had a question that was bugging me, and I looked up the relevant figure on Wikipedia. Wikipedia told me that he has a blog—a delightful blog about sailing in retirement, unrelated to the matter I had in mind. But that blog had an about page with an email address, so I wrote an email, and got a response right away.

From: Brendan (xorph@xorph.com)

To: ken@kensblog.comHello Mr. Williams! I’ve always wondered, why did you choose “on-line” for the original company name “On-Line Systems?” Was it derived from the idea of making software to be accessed on a mainframe through a terminal, or did the term mean something different to you at the time?

Thanks! Hope your seagoing adventures this year are wonderful.

—Brendan J

From: Ken Williams (ken@kensblog.com)

To: BrendanYou nailed it. Yes – I was doing freelance contract work on mainframe computers, specializing in large computer networks (literally on-line systems). When I started Sierra I kept the name I had been using for my contracting.

When we started getting larger I realized someone already owned the name and had to change our company name.

-Ken W

From: Brendan (xorph@xorph.com)

To: ken@kensblog.comIt’s so satisfying to have a clear answer to that after all these years. Thank you so much!

From: Ken Williams (ken@kensblog.com)

To: Brendan🙂👍

The exchange was months ago, but I continue to enjoy the pleasant feeling of this tiny conversation. I have other emails I have received in years past that I keep close in my heart, just because they caught me at a good moment with a kind word. Even without much social media in my life, I do talk to people in other ways online, via Izzzzi and Peach and sometimes (sigh) Discord. But a few lines of thoughtful outreach, one to one, carry a warmth and weight of meaning that is singular.

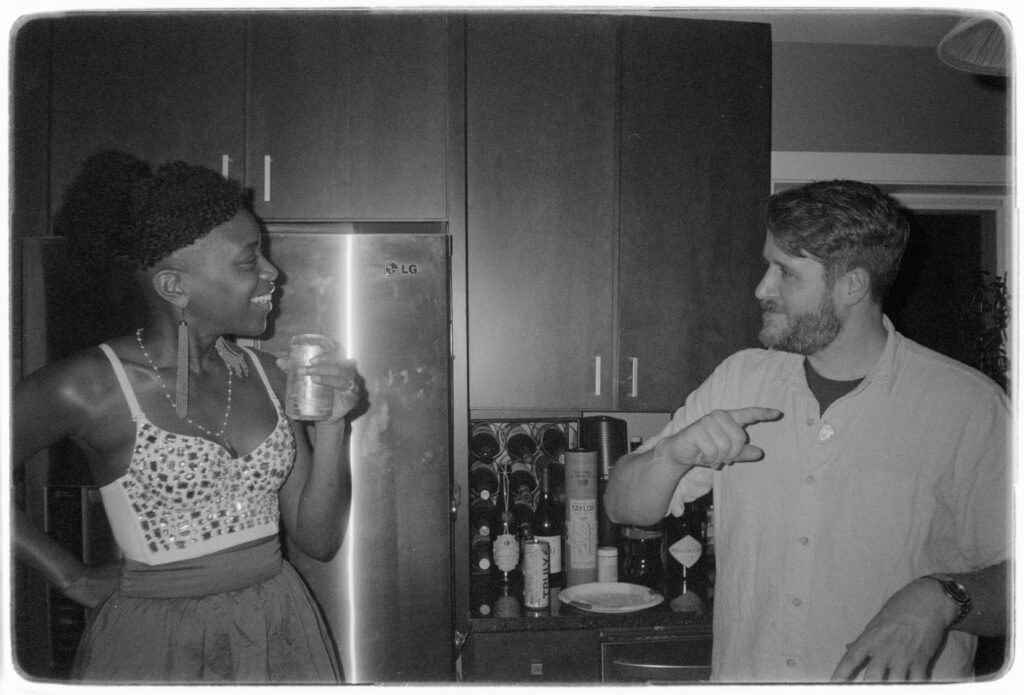

I’ve taken a lot of photos over the last couple of decades. In doing so I have learned that I’m not particularly adept in most genres. Landscape and street photography don’t come naturally to me, posed portraiture remains elusive, and things like sports or wildlife photography are far beyond my abilities. What I like shooting most are candids. They require at least a little skill, a little preparation, a watchful eye, and luck: I shoot a dozen for every picture that turns out the way I want it. But there is nothing like that moment of resolution, when I see on a screen that taking the shot has succeeded.

A photo doesn’t really make a moment permanent. Our photos are ephemeral, just like our selves. They still matter. Ephemeral connections, one to one, are the material we use to construct meaning in our own stories. You and I were born in a time when there is no other choice but to find our lives shaped by emails. So pick a shape you like, and put something in it that you want to see again.

We got a dog and his name is Max

Hello, friend. My opinions are my own and do not represent those of my employer, but over the summer we got to meet the best dog in the world. Our friends were fostering him from a local shelter, so we had a few opportunities to get to know him, and each time we loved him more. When we bought a house (oh, also we bought a house) and moved out of our apartment, we adopted him as soon as we had a place to put his bed.

Max is a small chihuahua derivation of uncertain age, probably around 10 or 11, and shortly before we took him in he was relieved of most of his teeth. He is friendly, quiet, sleepy and calm. He is not a lap dog, but he loves to take the center seat on our couch and place his small warm flank against a person’s thigh. Then he will nudge his little head under that person’s hand and insist on having his scalp massaged.

I am relying on Max quite a bit for mental health support of late. He did not apply for this job but he bears it with grace. Here are some photos of him.

A Walkable Internet

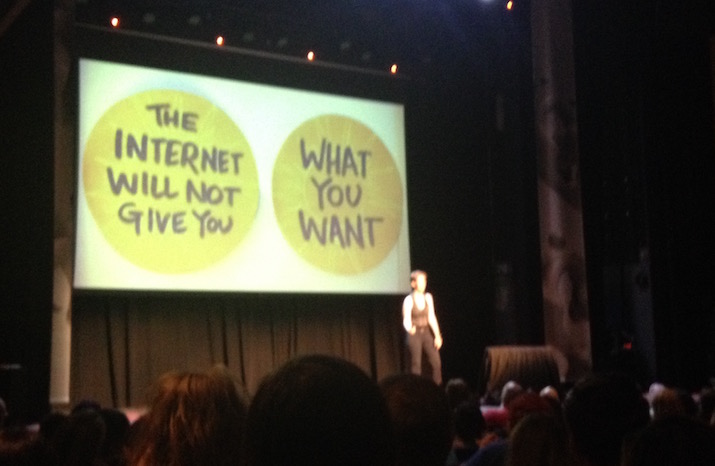

Sometimes I think that popular media’s fascination with counterintuitive propositions is a big contributor to what got us into this mess. I use the word “media” there to mean more than just major publications, but we’ll get to that later. Also, sometimes, I like to think up counterintuitive propositions myself, like software doesn’t mean “code,” it means “a system for consolidating control of the means of production.” Or maybe the Internet can be defined as “that which will promise you what you want.”

Photo by Stefan Shepherd from Lucy’s extraordinary September 2016 talk, which I think about at least every other day.

Photo by Stefan Shepherd from Lucy’s extraordinary September 2016 talk, which I think about at least every other day.

I don’t offer these takes with any intent to defend them. I just think they’re useful mental calisthenics, valuable as alternative modes of thought to the definitions that creep into common idiomatic use: things like the Internet can be defined as “the most active population of large social media platforms.” I certainly use that shorthand myself, often in a scornful tone, despite my own attempts to stretch the popular conception of the Internet around the deconglomerated approaches that people these days call “IndieWeb.” One of the writers I admire, and linked to back in March when talking about this stuff, is Derek Guy of Die, Workwear and Put This On. Sometimes I sneak onto Twitter to see his dorky fashion memes, and today I discovered this, one of his more popular tweets of late. It has, as of this writing, numbers underneath it that far exceed its author’s follower count.

the older i get, the more i realize that the most luxurious thing is being able to live in a walkable city. wearing a nice little outfit and walking 15 mins to buy just enough groceries for a single dinner will make you feel like Mrs. Dalloway going to the market

— derek guy (@dieworkwear) June 29, 2022

This is a gentle proposition, almost to the point of being anodyne. Maybe you disagree with it. I happen to agree, myself, as someone who has spent a number of years enjoying such a lifestyle; I agree in particular that it is luxurious, which is to say a luxury. One way I define luxury is an ephemeral privilege not to be taken for granted. Many people are systematically deprived of the privilege of walkability by the way that capital and its frequent servant, municipal policy, prioritize car travel and inherited wealth to create housing insecurity and food deserts. To me, that understanding seems built into the way these two sentences are constructed.

Three days after it was posted, I can sit here and watch the retweet and quote numbers on the post tick upward every time I breathe. I don’t think that’s due to positive attention.

twitter: touch grass

me: *goes outside to touch grass*

twitter: you ever consider people who don’t even have grass to touch? you idiot. you asshole. you absolute piece of shit.

— derek guy (@dieworkwear) June 30, 2022

i cant overstate how bad the internet has gotten in the last ~6 years. while there have always been dark places on the net, there used to be some level of good-natured camaraderie in specific circles. now every space feels primed for argument and bickering.

— derek guy (@dieworkwear) June 30, 2022

I’m not here to write about how Twitter Is Bad. Even Twitter, as a body, agrees that Twitter Is Bad. I’ve written variations on that theme for ten years as of next month, and I can’t declare myself piously abstemious from social media when I’m quoting social media posts in my post about social media. The interests of capital demand that Twitter makes its graph lines go up; the simplest mechanism to make them go up is to incentivize conflict; the capital circulates through organizations until the system’s design iterates toward conflict optimization. Primed for bickering, just as the man says. The story of social media is the story of how billionaires made other people figure out how they could extract money from the late-twentieth-century invention of the real-time flame war.

I just feel bad for Guy because I like his work and have a bit of a parasocial relationship with him: he is, more or less, the person who taught me how to enjoy shopping and wearing clothes. (I know many other people are subject to worse for less online, every day. I mean it when I say it’s Bad out there.) If not for Die, Workwear, I don’t think I would ever have chosen to take this series of self-portraits, a couple years back, wearing things I bought and liked just for myself.

I posted those photos on Flickr, even though I have my own IndieWeb site where I can host as many photos as I want. Flickr is a social media platform. It’s a rarity, not in that it did not generate for its acquiring capitalists the graph numbers they wanted, but in that it was then left to molder in neglect instead of being defenestrated for its failure. I have strong disagreements about some recent choices by its current owners, whatever their best intentions. But at least it’s not Instagram. Flickr has, for many years, retained an interface bent toward the humane and curious, instead of capitulating to the wind-tunnel abrasion of those who value human life less than the ascendance of the line on the graph.

Another thing I posted on Flickr, back in 2018, was the set of photos I took with Kat on our trip to Budapest together. One of the places we visited was Szimpla Kert, a romkocsma or “ruin bar,” built almost twenty years ago in what was once the city’s Jewish quarter by people in its neighborhood who wanted to make something new out of something old. It was once a condemned shell of a building; now it’s a huge draw, with thousands of visitors on a given night, most of whom are tourists like us. Locals might disagree, but I did not find that its charm was diminished by the crowd. It was idiosyncratic, vibrant, complex, and unique. Hungary—like my country, and like the Internet—is a more worrisome place to live than it was a few years ago. But Szimpla seems to be thriving, in large part because it is knit tightly into its local community.

“Szimpla Kert” translates to “simple garden.” I have a little experience with the allure of gardening, and also how much work a garden takes to maintain; I’m sure the people running Szimpla work very hard. But an interesting way of looking at a garden, to me, is a space for growth that you can only attempt to control.

In the middle of drafting this increasingly long post, Kat asked me if I wanted to take a walk up to her garden bed, which is part of a community plot a ways to the north of us. I was glad to agree. I helped water the tomatoes and the kale, and ate a sugar snap pea Kat grew herself right off its vine, and on the way back I picked up dinner from our favorite tiny takeout noodle place. It took over an hour to make the full loop and return home, and I was grateful for every step. An unhurried walk was exactly what my summer evening needed. I luxuriated in its languidness, because I could.

When you put something in a wind tunnel, you’re not doing so because you value the languid. I am far from the first person to say that maybe we could use a little more friction in the paths we take to interact with each other online. Friction can be hindering or even damaging, and certainly annoying; I’m not talking about the way we’ve somehow reinvented popup ads as newsletter bugboxes and notification requests. I just want to point out that friction is also how our feet (or assistive devices) interact with the ground. We can’t move ourselves forward without it.

It’s a privilege to have the skills, money, time and wherewithal to garden. You need all those kinds of privilege to run your own website, too. I think social media platforms sold us on the idea that they were making that privilege more equitable—that reducing friction was the same thing as increasing access. I don’t buy that anymore. I don’t want the path between my house and the noodle restaurant to be a conveyor belt or a water slide; I just want an urban design that means it’s not too far from me, with level pavement and curb cuts and some streets closed to cars on the way. I want a neighborhood that values its residents and itself.

This is why I’m as just interested in edifices like Szimpla Kert and Flickr as I am in the tildeverse and social CMS plugins and building the IndieWeb anew. Portland is the most walkable city I’ve lived in, and it ended up that way kind of by accident: the founders optimized for extra corner lots out of capitalist greed, but the emergent effect was a porous grid that leaves more space for walkers and wheelchairs and buses and bikes. The street finds its own uses for things, and people find their own uses for the street. Sometimes people close a street to traffic, at least for a little while. And sometimes people grow things there.

I don’t expect the Internet we know will ever stop pumping out accelerants for flame wars directed at people who just felt like saying something nice about a walk to the grocery store. That paradigm is working for the owners of the means of production, for now, though it’s also unsustainable in a frightening way. (I will never again look at a seething crowd, online or off, without thinking twice about the word “viral.”) But if someone who lives in Chicago can’t entirely ignore what suburban white people get up to in the Loop on St. Patrick’s Day, then one doesn’t have to go out of one’s way to join in, either.

I’m ready to move on from the Information Superhighway. I don’t even like regular superhighways. The Internet where I want to spend my time and attention is one that considers the pedestrian and unscaled, with well-knit links between the old and the new, with exploration and reclamation of disused spaces, and with affordances built to serve our digital neighbors. I’m willing to walk to get there.

A front-end developer and former colleague I admire once said, in a meeting, “I believe my first responsibility is to the network.” It was a striking statement, and one I have thought about often in the years since. That mode of thought has some solid reasoning behind it, including a finite drag-reduction plan I can support: winnowing redundant HTTP requests increases accessibility for people with limited bandwidth. But it’s also a useful mental calisthenic when applied to one’s own community, physical or digital. Each of us is a knot tying others together. The maintenance of those bonds is a job we can use machines to help with, but it is not a job I think we should cede to any platform whose interests are not our own.

The Internet will promise you what you want, and the Internet will not give it to you. Here I am, on the Internet, promising you that people wielding picnics have put a stop to superhighways before.

Photo by Diego Jimenez; all rights reserved.

Photo by Diego Jimenez; all rights reserved.

Fifteen years ago this summer, I was exercising a tremendous privilege by living and working in London, in the spare room of an apartment that belonged to friends I met online. They were part of a group that met regularly to walk between subway stations, tracing the tunnel route overground, which they called Tube Walks. There was no purpose to the trips except to get some fresh air, see some things one might not otherwise have seen, and post the photos one took on Flickr.

My five months south of the Thames were my first real experience of a walkable life. I grew up in suburbs, struggled without a car in Louisville, and then, for the first time, discovered a place where I could amble fifteen minutes to the little library, or the great big park, or the neighborhood market, which would sell me just enough groceries for a single dinner. Battersea is not a bourgeois neighborhood, but it’s rich in growth and in history. It changed what I wanted from my life.

London, like Budapest, like Chicago, is a city that has burned down before. People built it back up again, and they didn’t always improve things when they did. But it’s still there, still made up of neighborhoods, still full of old things and new things you could spend a lifetime discovering. And small things, too, growing out of the cracks, just to see how far they can get.

Daniel Burnham, who bears responsibility for much of the shape of post-fire Chicago, claimed inspiration from the city’s motto of Urbs in Horto: that is, City in a Garden. (Which I didn’t even know, myself, until Kat gently pointed it out to me while proofreading this post.) Burnham was also posthumously accorded the famous imperative to “make no little plans.” But I like little plans, defined as the plans I can see myself actually following.

I didn’t know where this post was going where I started it, and now it’s the longest thing I’ve ever published on this blog. If you read the whole thing, then please take a moment of your day and write me to tell me about a website that you make, or that you like, or that you want to exist. I’ll write back. More than ever, I want to reclaim my friendships from the machinery of media, and acknowledge directly the value that you give to my days.

Kara took about eighteen pictures of Lou Ferrigno at Emerald City this year because she was fascinated (not in a good way) with his biceps. I urged her to stop, having heard tales of Ferrigno’s anger at people who took his picture without paying–it is his only job, after all–but honestly, I think now I see what she was saying.

Credit for that picture to Josh Trujillo; you should click through to check out the gallery, which has cute kids in costumes.